First up, news.

I’ve observed in my long, Gen Z life that as soon as you give yourself something to do, it will set off a chain reaction and more and more things will suddenly start piling on top of it. Which is good, since I like being busy, but does mean that you go from zero responsibly (aka quarter-life crisis, see the about section) to HEAPS OF COOL STUFF HAPPENING all at once.

The main hunk of cool stuff is my new job – first industry job, unless you count the acting gigs I had in 2008, which I decidedly do not. This real, not-for-children job is with the marketing department for an arthouse cinema in Melbourne, and will involve lots of creativity, industry knowledge, and free popcorn. Essentially, it’s a dream job, and I couldn’t be more excited about it. They’re paying me and everything!

The other main gem in the cool stuff pile is my honours degree in film and cultural studies, which I’m going ahead with part-time: coursework in 2020 and thesis in 2021. Which means two more years of studying (hooray), spending time at uni (yippee) and student discounts (PRAISE THE LORD).

If you’ve noticed a theme, well done: 2020 is going to be a year where I do a truly insane amount of writing about movies. I’m planning to keep going with this little project anyway, because it would be pretty sad to back out before January’s even over, but please be forgiving if there are some sparse, late or grumpy pieces here and there.

LIFE UPDATE OVER.

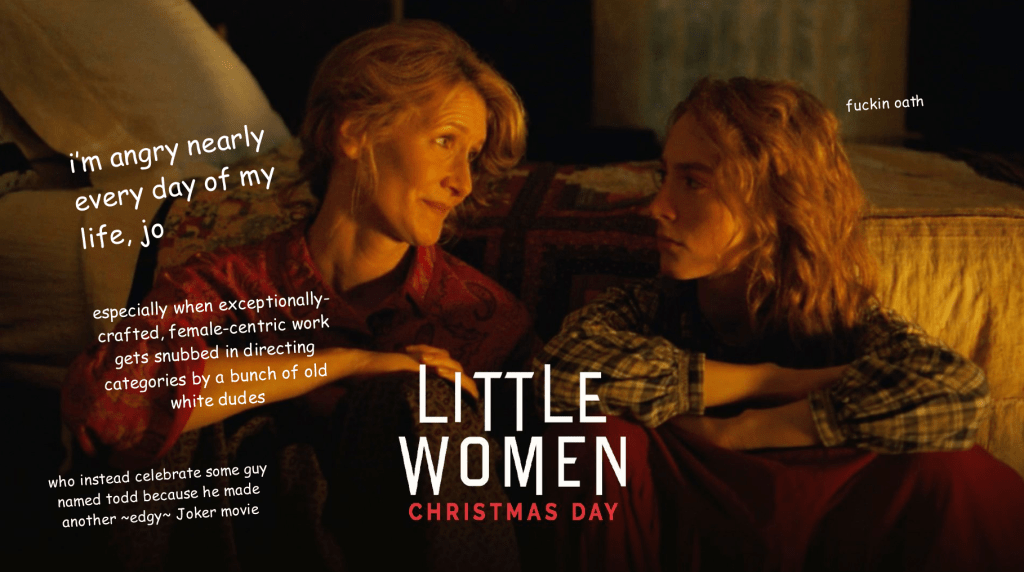

This felt like an appropriate review to preface with a few paragraphs of build-up, because my build-up towards seeing Little Women is finally over. Oh boy, was it worth the wait.

Louisa May Alcott’s 1868 novel has been adapted countless times since its publication, and the consensus of many was that this civil war family tale had already been wrung dry. My quasi-religious faith in the deity that is Greta Gerwig told me otherwise, and I was absolutely right – I’ve never a particularly dedicated fan of the novel, and this version made me feel that I ‘get’ Little Women in a way I never have before.

One of the common issues with the novel is the dissonance between its fun, whimsical, girls-growing-up-together-and-having-shenanigans beginning, and the increasingly bleak ending as everyone ends up separated, away from home and promptly, passionlessly married off. Alcott reportedly engineered this dissatisfying conclusion on purpose, writing in a letter that she was so frustrated with the expectations of her audience and publishers that she created a “funny”, ridiculous match to marry Jo off to “out of perversity”.

Gerwig cleverly negates this descent into depression by layering these two parts over each other, creating two timelines which regularly flash back and forth. We begin with an adult Jo (Saoirse Ronan) selling stories in New York, and are gradually treated to flashbacks of her childhood and family until these flashbacks make up the bulk of the plot. I found myself craving these warm, cozy scenes of youth, and quickly realised that this is all part of Gerwig’s design – the film tantalises us with short snippets of sepia-toned happiness, scenes which get longer and less warm until the line between childhood and adulthood has blurred beyond recognition.

This deft restructuring is aided further by a remarkably flexible and charming cast, who have the added challenge of playing two different versions of their characters. It almost goes without saying that Saoirse Ronan is astonishing, playing Jo with the perfect balance of power, vitality, anger and vulnerability. Ronan apparently begged Gerwig for the role, who, after Lady Bird (2017), likely didn’t take much convincing.

The wonderful Laura Dern is muted but effective as the long-suffering Marmee, not to mention shockingly believable as Ronan’s mother. Despite similarly lovely turns from much of the supporting cast – Chalamet (playing Laurie) is more charming than I’ve ever seen him before – the biggest revelation here is Florence Pugh, a breakout star of 2019 who totally revitalises the historically loathed character of Amy March.

Pugh truly steals the show, building up an Amy who is hilarious, sassy and spoilt (“I have such lovely small feet!”) but also strong, practical and deeply likeable. Crucially, Gerwig chooses not to punish Amy for her candour and ambition, but instead provides her with a vicious, powerful monologue about the lack of agency for women in her time. Jo may be the rulebreaker, but Amy is determined to play the game as best she can, and end up on top. In this new Little Women, Amy being married off to Laurie is no longer a cruel jab for romantic readers, but an earned and satisfying conclusion for two characters who are so often denied.

Much of the film’s feminist theme feels poignant and especially timely in the wake of the 2019 Oscar nominations, and Gerwig’s lack of nomination for Best Director – a category which has only ever seen five female nominees, and a single win. Professor Bhaer (Louis Garrel) makes some early, foreshadow-y metacommentary about authors and artists smuggling big ideas into mainstream, accessible work. This notion of ‘taking the system down from the inside’ later becomes especially excellent in the film’s masterful ending, which I don’t want to over-explain – I’d undoubtedly be copying other great breakdowns. Suffice it to say that the condensing of Jo, Alcott and Gerwig into one creative force provided, for me, the cleverest and most affecting turn of anything I’ve seen for a long time.

Similarly tongue-in-cheek dialogue about what is deemed ‘important’ enough to write about – or whether the act of writing itself is enough to confer importance – feels especially sharp. In a year where, as provocatively claimed by a recent SNL sketch, all the other Best Picture nominees are essentially about ‘male rage’, the centrality of womanhood in Little Women is powerfully cathartic. The warmth and lushness of the March home, particularly in scenes of meal times or family reunions, positions domesticity and family as both powerful and sacred in Gerwig’s vision. An overtly utopic final scene forefronts children, family and togetherness as the ultimate success, as if to suggest that these women will become uniquely responsible for building the world’s future. Maybe Alcott wasn’t thinking “the future is female” when she was writing in the nineteenth century, but it’s somehow drawn from her words – this is a period piece with a thoroughly modern sensibility.

I’m hoping to do my thesis in adaptation studies, meaning I’ll likely be revisiting this film in the future. One thing I’ve gotten increasingly confident about is that great adaptations, particularly of classic literature, can’t afford to just reproduce what’s on the page – they have to actively engage with the soul of the text, and do whatever they can to transcribe that essence from word to screen.

It feels undeniably modern, and maybe it’s a tale as old as time, but Gerwig, in her subtle deviations from Alcott’s text, makes Little Women somehow more true than it’s ever been before.

And, since I need to go and figure out what ‘smart casual’ means, that’s a suggestion to unpack further some other time.

7/7. Sublime.

P.S. I do have one criticism – this film is long, and it does sometimes feel it. But if Quentin Tarantino can make a 161-minute film about people wandering around in 60’s Hollywood and everyone is going to lose their shit for it, Our Lord and Saviour Greta Gerwig can take up two hours of your time.